With 8 days left on duncan’s holiday we spent two nights in Kathmandu, an infamous final destination for many overlanders arriving after months in Central Asia and China, starved of Western cuisine and company. We also met up with Karma Sherpa, a friend of a friend of Duncan’s family. Dawa Sherpa, the first hand friend, has known Duncan’s sister for many years since she was one of his first guiding clients. Both Karma and Dawa are Sherpas from the Everest region of Nepal, the region that has produced some of the world’s greatest high altitude climbers. Karma’s brother holds the record for the longest period spent on the top of Mount Everest at 21 hours, this feat occurring on his second summiting of Everest that year. Karma, Dawa and their families became good friends during our stay and were a mine of information about all things Nepali.

After so long bound to our car in freezing temperatures we chose a relatively short, low-level trek. The Helambu trek barely gets above 3000m and can be done in 7days without serious pushing. Starting just outside Kathmandu the route spends most of its time ascending and descending, sometimes several times a day, through extraordinary terraced farmland. Each small step like a garden in itself, ringed by flowers, grasses, trees and bushes. Seen from a distance the terraces create contoured order out of the chaos of peaks, ridges and small river valleys.

As the path follows the ridge line for most of its length it connects up many small villages, sometimes just a family’s few dwellings and sometimes 20-30 or so homes arranged along a ridge or in the centre of a bowl of terraces. Building style varies depending on the region and local materials, however all are impeccably clean and well ordered and make good use of the sun and views. Some also serve as guest houses and are numerous enough to make independent trekking a breeze with little more than a change of clothing and a sleeping bag required. Meals hardly vary being mostly based on rice, dahl, potato and occasional egg for breakfast, however prices vary strongly with altitude and distance from supply. All food must be carried in, usually by local porters in bamboo baskets hung by a fabric belt around the forehead. The price of tea in particular was artificially inflated, and as a necessary staple for any trekker we felt this was grossly unfair profiteering, however guest house owners were deaf to our bargaining insisting that this remain one of their few sources of profit.

When not ferrying supplies the porters acted as pack mules for supported camping treks, one couple we repeatedly met having 8 porters, including two cooks and a guide to support their week-long adventure. Porters are usually paid a single wage for a load of 15-20kg, some can claim double wages for carrying twice this load and as a result we saw some extraordinary packs being carried on short, tough, be-sandalled legs.

In the event the trek seemed to us to be a tough test of stamina, more for the constant ascent and descents than the distance covered. More experienced Duncan swore that our choice of apparently easy going trek was tougher than the mammoth Annapurna Circuit, however this might have as much to do with his personal fitness after years out of a rowing boat rather than objective recollection. Certainly by the end of our week eating vast portions of rice and lentils, early starts and early nights we felt that we had removed whatever car-bugs our bodies had accumulated.

Following our trek and another day in Kathmandu Duncan waved goodbye for his protracted flights back to Sydney. We spent a few more days in Kathmandu, servicing the Landy and trying to make sense of the confusion of Hindu temples and Buddhist Stupas. The abiding images of Kathmandu are a complex blend of narrow streets, colour, noise and confusion in a city bursting with humanity at its geographically constrained seams.

We took one side trip out of Kathmandu before leaving, to Bhaktapur: an ancient Nepali capital and site of an artful bomb site of palaces, Hindu Temples, shrines and iconography. Some of the shrines display some very imaginative top-shelf erotica carved into the eaves. Elsewhere in this ancient and religious melee were Thanka painters; hawkers; blood sacrifices with eager Nikon-toting tourist scarpering around the fringes for the perfect shot of ritual slaughter; sinister-sounding drums; street dogs and puppies equally adorable and pitiful. All of which proved too much for one afternoon after our more earthy experiences of previous weeks.

Our first stop after Kathmandu, Bandipur, is 7km more of less straight up off the main highway and is a gem of old Nepalese wealth, lying as it does on an obvious trade route between Nepal and Tibet. This trade route has clearly dwindled and been superceded, however the village has reinvented itself to welcome tourism to its merchants’ homes overlooking terraces and Himalayan vistas. We spent our short stay wandering around the village and achievable walks in the region, generally basking in the easy sights and friendliness of village life.

We arrived the next day in Pokhara, stopping off only for lunch of smoked fish caught and sold from the roadside. Pokhara is significantly smaller and more relaxed than Kathmandu and is the base for many of Nepal’s longer treks in the Annapurna region. The immense presence of the surrounding mountains as well as its stable weather makes it one of the world’s prime Paragliding spots, with flocks of wings colouring the sky just around the corner from the main town. Nepal paragliding is also famous for the giant birds of prey that join the gliders in searching out the thermals. Some come from a local bird sanctuary and have been trained to fly to the glove during flight, something that brings a lot more meaning to the sport than simple flying.

The main tourist area is based around the lake, which is dotted with guest houses and cafes filled with travelers either preparing for a trek or just recovering from a couple of months’ battling their way through India. There are many opportunities for extraordinary views of the Annapurna range from the hills surrounding the town although each time we made an effort to experience them the day would inevitably be overcast with only occasional glimpses through cloud peepholes of the midrift of a mountain.

On one of these excursions we picked up two local children, Sandeep and Kumar, who tagged along so trustingly we hardly felt we could turn them back against their will. Having got as far as the Peace Pagoda on the opposite side of the lake, well beyond Sandeep and Kumar’s usual exploration reach, we eventually felt we had reached the threshold beyond which any 8 year old’s mother would worry about abduction. So rather than continue around the rest of the lake we dropped to the lakeshore and hired a rowing boat to take us back to the opposite bank, depositing the kids back where we had found them. They turned up often in the next few days, adopting us and the parked landy as their own such that we often found wing mirrors bent out of position or impossible footprints on their favourite climbing frame.

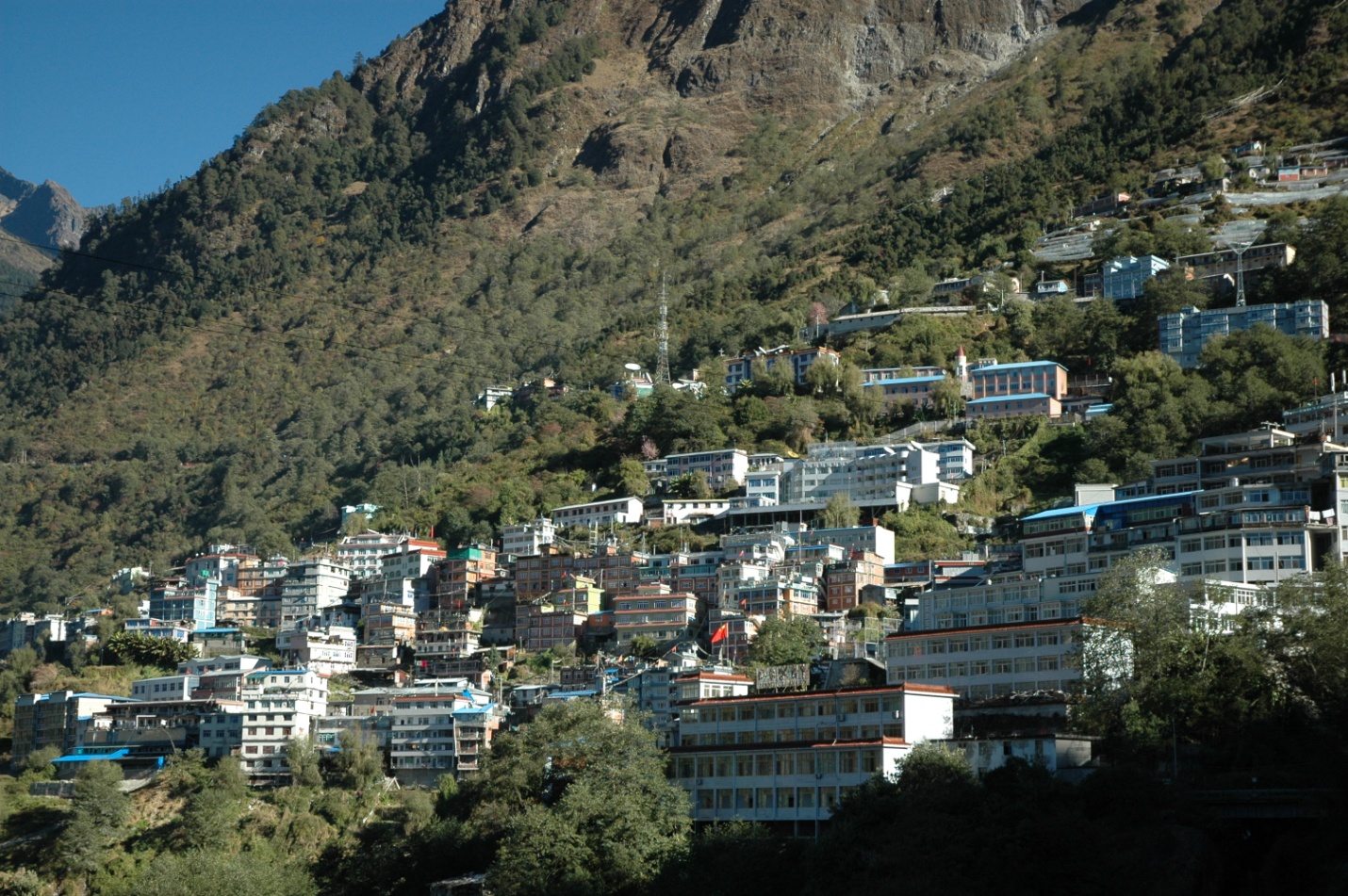

After Pokhara we set off again aiming in a meandering fashion for the Indian border. Our first day’s driving took us through one of the most dangerous roads in Nepal with shrines each end to offer prayers for safe deliverance from the twin evils of never-ending corners around precipitous drops and other drivers. The corners and constant changes in altitude soon took on their own rhythm against the dramatic scenery, however the other drivers were a constant menace with two of our closest incidents of the trip – one a small car clearly surprised by his own incapability to corner and the other a more threatening 4x4 asleep at the wheel. However, we clearly made it and took a turn off the road to stay at Tansen, a small town on the fringe of the lowland Terrai region of Nepal.

Tansen is far from a tourist ghetto and offers a relief from that unreality. Ruth used the stop to buy her first Salwar Kameez, first buying the fabric and then contracting a tailor to mould the fabric to the specifications largely given by the old lady who sold the material and who did not approve of any show of immodesty. For a traditional outfit this is a surprisingly complex process with as many variables as there are body shapes, fashions and prejudices. In the end we spent considerably more on modifications than the £4 paid for the outfit.

We spent the rest of our stay in the region on a two day trek through friendly local villages to the palace, built by a local Prince as a memorial for his deceased wife. We spent much of the evening with 8 teenagers escaped from their parents for an annual weekend of rough camping with locally brewed rice beer and chicken masala. In a parody of British teenage house parties they obediently queued up at the guest house satellite phone that evening, each claiming to their concerned mothers to be spending the night at the previous caller’s home. One in particular was initially very keen on Ruth, so much so that it was constantly necessary to obstruct his advances in a bizarre anti—courtship dance. It was only when he discovered her immense age, apparently 3 years beyond acceptable Nepalese marriage vintage, that he retreated with pride intact. After their high spirits and bravado of the night before we found them the next morning shrinking and shivering in their underwear having washed their slept-in trousers in preparation of confrontation with their mothers.

We were delayed from leaving the following day by a transport strike, a depressingly familiar action called by a Maoist party still making its stumbling transition from militant trouble makers to politicians. Once the roads had been opened to traffic we waved goodbye to the family of Anjani Shrestha we had been staying with and made our halting way to Chitwan National Park. We hesitated once in the journey when we came to a long queue of mostly trucks. With no direction or explanation given by either other drivers or police we stumbled past until we came to a half-collapsed bridge that a truck had recently collided with. The other trucks were patiently waiting for a ford to be made in the river below, however we were waved across the sagging tarmac by a beamingly confident police man.

We stayed just outside Chitwan in a guest house run by a Swiss expat and his Nepalese business partner. The park itself is a vast lowland expanse of hills, jungle and grasses with a slow river winding through. It used to be a favourite hunting ground of kings and is now the protected home of elephants, tigers, rhinos, alligators and other things big and small. We spent two days taking it in and enjoying activities such as washing the elephants, visiting the baby elephants in the breeding centre, watching the elephants play football and riding the elephants through the jungle to see a happy gaggle of rhinos, apparently oblivious to us and the elephants. After such an elephant-overdose Ruth is still insisting on adding one to her dream collection currently including puppies, children and pygmy goats.

After Chitwan we were sorry to be on our way again and on the verge of leaving Nepal, a wonderfully engaging country, at times almost naïve in its show of colour, sound and happy emotion.